There's rosemary, that's for remembrance;Pray, love, remember: and there is pansies. That's for thoughts.

There's fennel for you, and columbines:There's rue for you; and here's some for me:We may call it herb-grace o' Sundays:O you must wear your rue with a difference.There's a daisy: I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died.Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act IV Scene V

Ophelia knew of what she spoke, even in her madness.

Symbolic meanings have long been attached to flowers, but it was not until Lady

Mary Wortley Montagu and Aubry de La Mottraye introduced floriography into

England and Sweden respectively, in the early eighteenth century from Ottoman

Turkey, that the practice took hold in the popular European imagination, as part

of the new craze for all things Orientalist.

|

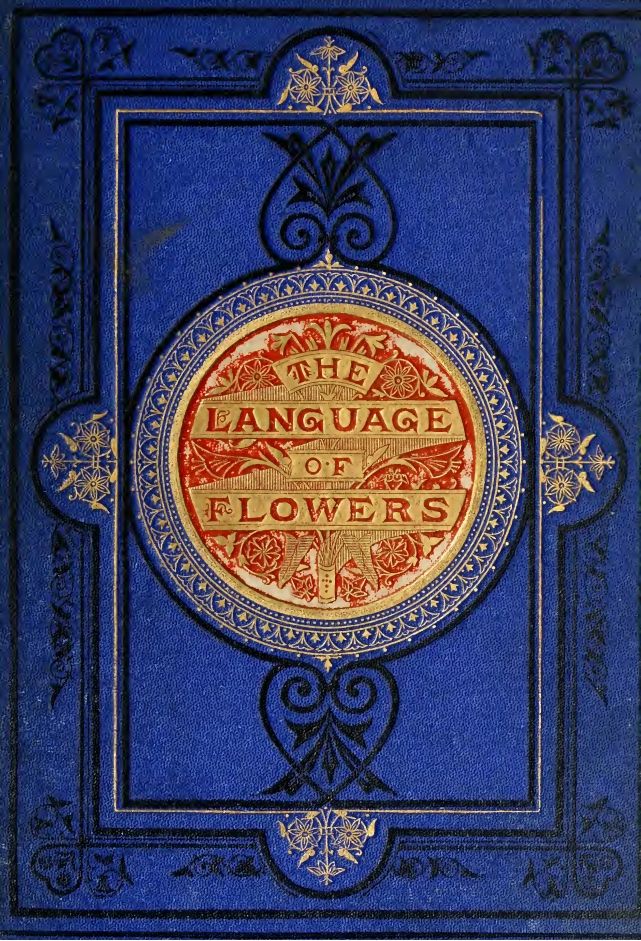

| Robert Tyas - The Language of Flowers |

Before long, the scant

descriptions of Montagu and La Mottraye were added to by a long series of

writers, from Louise Cortambert’s Le Language des Fleurs (1819), through

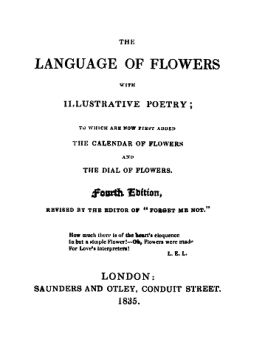

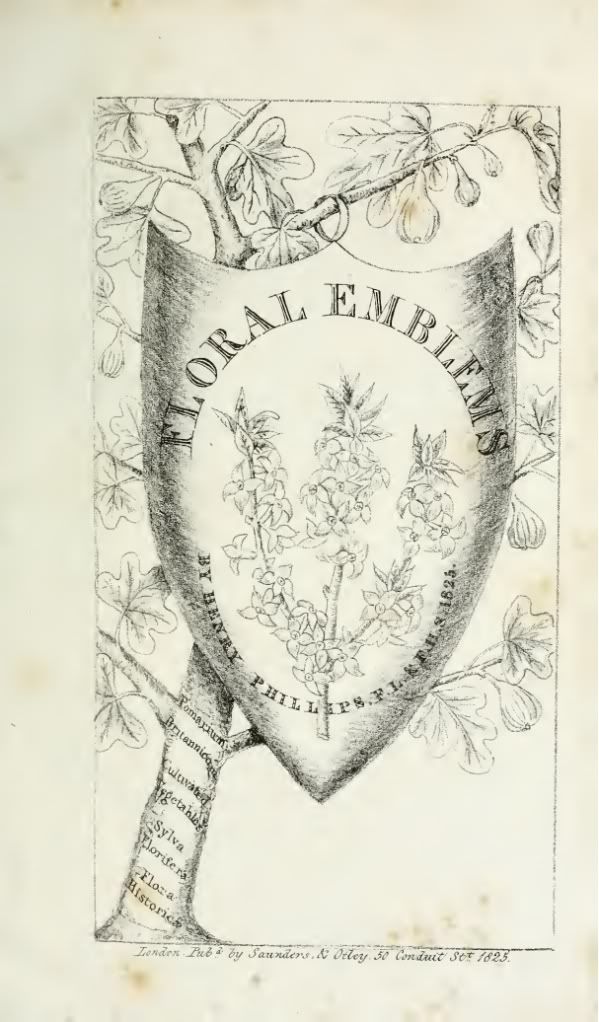

Henry Phillips’ Floral Emblems (1825), Frederic Shoberl’s Language of

Flowers (1834) and Robert Tyas’ Sentiment of Flowers (1836), with an

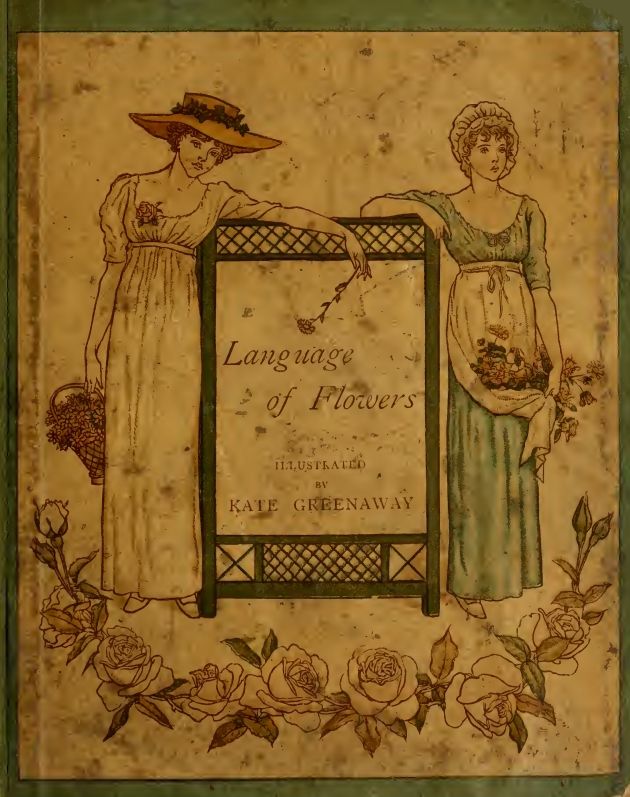

immensely popular edition published by Routledge and illustrated by Kate

Greenaway in 1884.

|

| Language of Flowers - illustrated by Kate Greenaway |

A popular method of describing the meanings of individual

flowers was the weekly or monthly columns published in magazines and

newspapers, which could run over several years without repeating themselves.

With such an immense field, there were bound to be conflicting interpretations

of the plants and flowers, although in time a general consensus of opinion

emerged.

|

| Frederic Shoberl - The Language of Flowers - 1835 |

The strength of the medium lay in the ability to use the various

individual blooms and plants in combination, thereby producing a ‘phrase’

derived from the meanings of the separate flowers, with the whole being greater

than the individual parts.

|

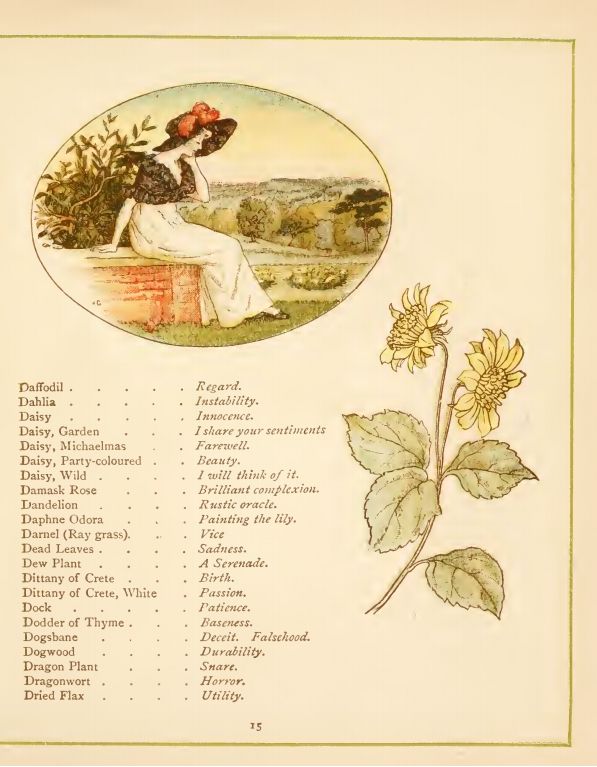

| Page from Greenaway's Language of Flowers |

Thus it was possible to send very subtle and precise

messages within a single bouquet, declaring nuances of love and devotion,

friendship and sympathy, joy, piety, hope, despair, through to outright

animosity and hatred. Fresh flowers betrayed the immediacy of the message, and

news and thoughts could be conveyed without inking one’s fingers.

|

| Crown Imperial, Turk's cap Lily and Lily of the Valley |

This

illustration, from Flora’s Lexicon by Catharine H Waterman (1855), show

a combination of a Crown Imperial, Turk’s Cap Lily and Lily of the Valley,

which carries the meaning, ‘You have the power to restore me to happiness’.

|

| Forget-me-not, Hawthorn and Lily of the Valley |

Another example, from Robert Tyas’s The Language of Flowers or Floral

Emblems (1869), has Hawthorn, Forget-me-not and Lily of the Valley combined

to give the sentiment to a departing loved one, ‘Forget-me-not! in that

rests my hope for the return of happiness.’

|

| Lilacs, Marvel of Peru and Spiderwort |

From the same work, a plate

showing Lilacs (Purple and White), Marvel of Peru and Spiderwort illustrates

fear and hope alternating in the mind of a youthful aspirant to beauty's

favour, ‘Youthful love is timid, and yields but transient pleasure'.

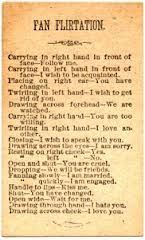

Even the presentation of the flowers within the bouquet carried meaning; a

rosebud or other thorny stem presented bearing both leaves and thorns meant ‘I

fear but I hope’, if both leaves and thorns were removed, it became a

warning, ‘neither to fear nor hope’, whereas taking away the thorns

meant, ‘there is nothing to fear’, but removing the leaves and keeping

only the thorns said, ‘there is everything to fear’.

|

| Rose, Ivy, Myrtle - To Beauty, Friendship and Love |

And within the

bouquet itself, there was meaning. A flower presented with its leaves intact

meant a positive affirmation of its meaning, but taking off the leaves meant

that the negative sentiment was intended; in flowerless plants, cutting off the

tops of the leaves carried the same intent. When a flower is inclined to the

left, the pronoun ‘I’ is intended, when it inclines to the right, ‘thou’ is

meant; when tying a ribbon or silk band to a stem, a knot to left as you look

at it means ‘I’ or ‘me’, a knot to the front means ‘thou’ or ‘thee’. If an

answer to a question is being sent, a flower placed on the right replies in the

affirmative, on the left means a negative answer.

|

| Henry Phillips - Floral Emblems - 1825 |

When worn on the body, a

flower placed on the head means ‘caution’, on the breast it means ‘remembrance’

or ‘friendship’, and over the heart means ‘love’. To modern tastes, some of the

meanings seem reasonable enough – beauty by the full-blown rose, oblivion by a

poppy, glory by the laurel and peace by the olive, but others seem odd, to say

the least. How about sending your love a cabbage (profit), a potato

(benevolence) or a pineapple (you are perfect)?

|

| Page from Greenaway's Language of Flowers |

Of course, if the messages were

as well known now as they were then, it would not seem in the least bit strange

and everything would be tickety-boo and, let’s face, it is a all little bit more

inventive and romantic than a dozen red roses on St Valentine’s Day or a mixed bunch of

scrawny dahlias, leggy carnations and an unidentifiable stalk of greenery

snatched at the last minute from a late-night filling station when you’ve

forgotten her birthday. Again.